The Greatest Heist in History? The Captain of Kopenick November 7, 2012

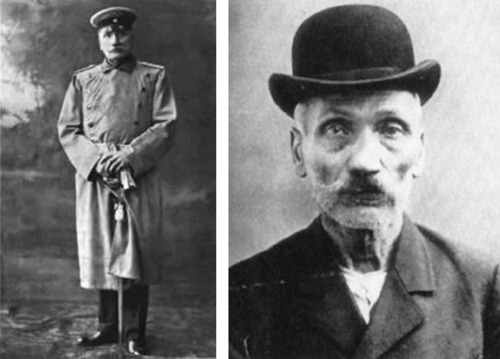

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackMuch has Beach travelled in the realms of criminal gold. But rarely has he come across a villain of the quality of Wilhelm Voigt (obit 1922): the Captain of Kopenick. Let’s begin with the shocked aftermath and then follow Voigt back through one of the most daring robberies in history.

17 October 1906 the German police published the following description of a most unusual miscreant:

[the wanted man] is about 45 to 50 years old and has an approximate size of 1.75 metres. He is of slim build, has a thick, grey, drooping moustache and a shaved chin. The face is wide, and one cheekbone protrudes, giving the face a lopsided appearance. The nose is smashed in, and the legs are bent slightly outwards (so-called bow legs). The stance is slanted to the front, with one shoulder slightly sticking out in the back, so that this figure, also, appears crooked. He was dressed in an infantry uniform, hat, a paletot with the rank insignia of a Captain of the 1. Garde-Regiment zu Fuß , long trousers, high boots with spurs, white gloves, and a sash. He carried an officer’s rapier with a star badge.

Smashed noses and drooping moustaches can, of course, be found in thousands of mug shots from around the world: in some criminal fraternities they are practically de rigeur. Likewise the bow legs might suggest rickets and birth in the poorer classes: but a rapier and a star badge and a paletot? Wth!?

Let us go back further now to 16 October 1906 and the little town of Kopenick (aka Koepenick or Köpenick) some twelve miles from Berlin, on the idylic Spree river. At this date the town had about twenty thousand burghers and was thought beautiful enough that Berliners would take day trips there. It is early afternoon and a man with a smashed nose, bow legs and a droopy moustache – our hero – has just arrived with twelve soldiers commandeered from a shooting range in nearby Plotzensee. The comedy is about to begin.

On arrival, the ‘captain’ ordered [the soldiers] to load their guns and to put on their bayonets; and to the amazement of the population he occupied with his little troop the town hall, whose issues were carefully guarded. He was acting in virtue of an order from the Emperor’s Cabinet, to which the police submitted without making any further explanations. The ‘captain’ ordered the offices of the mayor and treasurer to be opened to him. The population had gathered on the square before the town hall whilst the gendarmes were holding back the crowd. The ‘captain’ ordered the mayor to close his accounts, and to hand over to him the municipal treasury, which amounted to four thousand and two marks. But there was a deficiency of one mark. With the presence of mind which he maintained to the end, the ‘captain’ had a statement drawn up, and ordered the cashier to seal the bag containing the money, which by superior orders he had to remove to Berlin.

The captain did not let his mask slip for a moment. He seems to have enjoyed rubbing the noses of the high and mighty in every cow pat that he found along the way, even using the great von Moltke as a stage extra in his little play. Oh to have been there when the furious General walked onto the train platform…

The mayor and the treasurer were then conducted under military escort to their respective domiciles, where cabs, summoned by the police, were waiting to take them to Berlin. The wife of the mayor refused to be separated from her husband, and she took a seat with him in the cab. The brigadier of police took a seat in front of them and a grenadier took a place beside the cabman. The same procedure was followed with regard to the treasurer, and the two cabs started for the Berlin army headquarters, where the ‘captain’ arranged to join the prisoners, whilst he himself was leaving by rail. When the cabs stopped in Berlin before the sentry at Unter den Linden, their arrival caused great sensation, and the officer on duty immediately telephoned to headquarters. The commander of Berlin, General von Moltke, arrived at once, and the mystery was discovered. The audacious ‘captain’ had disappeared.

‘The Captain’, William Voigt was captured within ten days and sentenced to four years in prison, being released after two: the Prussians were pretty lenient all things considered. But his exploit was already an international sensation and Voigt himself became a folk hero. Any amusement to be wrung out of this incident though was ruined by self-satisfied Anglo-Saxon (particularly British) banter about how only the militarised Prussians would fall for a trick like this. G.K.Chesterton pontificated on the matter in All Things Considered and here is the normally sensible Sarolea:

It requires a stretch of imagination which exceeds the power of a jejune Englishman to realize that such an incident should have been possible in a capital of two million people at the beginning of the twentieth century. How is an insular Englishman to conceive of a burglar, merely because he has donned an officer’s uniform, entering a town hall in glaring daylight; arresting the mayor and officials; ordering the books and the municipal treasury to be handed over to him; sending the magistrates to prison in a cab; and finally, walking away with the spoils, without having his authority once questioned by the bewildered but obedient municipal officers. In other countries such an incident would belong to comic opera [in fact the incident became a musical, a play and later a film]. In Prussia it reveals the tragedy of despotism, the total absence of political initiative, the perversion of popular character, and the passive obedience of an unpolitical nation which yet claims to rule supreme over the civilized world.

Beach is presently looking for parallels from the English-speaking world: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com Anything to prove Chesterton wrong. He’s got plenty from the continent.

***

13 Nov 2012: Louis makes a cute comparison before we Brits get all superior: Isn’t there this tale about some practical jokers who made a visit to the HMS Dreadnought, claiming to be the sultan of someweherefaroff, and his retinue, on a state visit? Sounds to me, that this is the the same thing…. I found this on Wiki: From 1907–1911, Dreadnought served as flagship of the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet.[41] In 1910, she attracted the attention of notorious hoaxer Horace de Vere Cole, who persuaded the Royal Navy to arrange for a party of Abyssinian royals to be given a tour of a ship. In reality, the “Abyssinian royals” were some of Cole’s friends in blackface and disguise, including a young Virginia Woolf and her Bloomsbury Group friends; it became known as the Dreadnought hoax. Cole had picked Dreadnought because she was at that time the most prominent and visible symbol of Britain’s naval might.’ Louis writes also ‘I seem to remember that the Captain, after his release, played himself in a play based on his exploits’. Thanks Louis!

20 Nov 2012: Kit writes ‘The story about Kopenick and the British treatment of the story took me straight back to my own reaction (Anglo-Saxon type Aussie) to first hearing of the Teigin Bank Robbery. Japan 1948 Man claiming to be from the “Public Health Office” shows up at a bank and tells the staff he is here to deliver an inoculation against some disease or other. The man is wearing an “official” armband so they obediently comply. As i heard it, the staff all go to the lunch room and wash their own tea cups and then line up to receive the antidote. Of course, rather than medicine, they are administered cyanide and the robber/murderer then proceeds to plunder the safe. Wikepedia has the bare details under major Japanese crimes and Sadamichi Hirasawa: The story was told to me in mixed company, in Japan. A Japanese guy provided the facts (it is still a relatively well-known case) and and an English speaking expat provided the commentary. In his view it was a perfect example of how a totalitarian society (30’s and 40’s Japan) bred compliance and blind obedience, and furthermore illustrated the Japanese people’s willingness to blindly follow orders. I could see though, in my Japanese friend’s eyes, a hurt look. He saw it differently, I think. When the British press reported the Kopenick story, they were on a pre-war footing and were keen to characterize the Germans as different and therefore dangerous. Perhaps the Prussians in your story saw the heist as an example of someone exploiting a strength in the social system (obedience) for their own nefarious ends. It is certain that any lingering folk knowledge of the Kopenick case emphasizes the evil of the bad guy, not the gullibility of the townsfolk. In my view, Japanese society then and now values trust in authority, and their story is not a parable about passive obedience, but rather one of how rotten apples can turn up in even the purest barrel.’ Thanks Kit!!