Whoops, Apocalypse! October 18, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback***Dedicated to Andy the Mad Monk, who suggested this topic***

When, 6 August 1945, the pilot Paul Tibbets revved up Enola Gay on the island of Tinian everyone on the ground held their breath. Since the bomb, Little Boy, had arrived those in the know had understood that should it accidentally explode most human life on the island, a mere thirty-nine square miles in size, would cease to exist. A particularly dangerous moment was the take off. If Enola Gay veered on the run way or aborted the run… Well, it might easily be game over.

As it was Enola Gay completed its mission and made it back home. But over the next decades there would be many planes that took off and landed carrying atom bombs and nuclear weapons, particularly once America needed bombers in the air at all times for purposes of deterrence. How long would it be before something went horribly wrong?

The first recorded instance of a nuclear-bomb accident dates to 1950 when a US B36 bomber travelled with a weapon from Alaska to Texas: they were on a practice bombing run against San Francisco (wth!). The plane had mechanical difficulties – three engines out of four stopped working – and the crew had to jettison the bomb off the Canadian coast. The bomb exploded on its way down.

Luckily for the USAF and for British Columbia the bomb had been a dummy with uranium but no plutonium. However, future nuclear screw ups were to prove far more dangerous. Beach’s personal favourite is the bombing of South Carolina 11 March 1958. Here is a summary from a recent Daily Mail report in the you-couldn’t-make-it-up file.

The captain of the bomber, Bruce Kulka, decided to go into the aircraft’s bomb bay to look at the weapon after difficulties during the flight with its locking pin. But the unfortunate captain had no idea where to find the locking pin in the bomb release mechanism. He searched for the pin for 12 minutes before rightly realizing it was high up in the bomb bay. He jumped up to see where he thought the locking pin was but unfortunately chose the emergency bomb-release mechanism for his handhold.

The bomb fell to the ground at Mars Bluff leaving a 50 foot wide and 35 foot wide crater: luckily (a word repeated several times in these accounts) no one was killed. And the nuclear core had been kept elsewhere on the plane. But it was only a matter of time before an armed nuclear missile or an entire plane, bomb and nuclear core went down together.

This leads us to the two worst examples known to the general public.

24 January 1961 could have made it into the files of infamy, trumping 11 September 2001 several thousand times over. A B52-G was flying off the south-eastern coast of the US when a fuel leak was detected. In retrospect, foolishly, the plane with two fully-functional – controversial – nuclear missiles was directed to land at Seymour Johnson Air Base. The mechanical problems though intensified and the crew were forced to eject as the plane span out of control over Goldsboro, North Carolina.

Don’t believe in angels or a benevolent personal God? This author doesn’t either. But events like this do make you think. Both bombs separated from the plane as it came down. One plunged into the ground and buried itself tens of feet into the mud. It is still there today… It did not go off and it is safe in as much as there will not be a thermo-nuclear explosion: though would you eat any corn from that field? Far more serious was the second bomb, whose parachute opened. The bomb then did what nuclear bombs are supposed to do: it prepared to kill a lot of Commies (in North Carolina?!) and ran merrily through various fail safes. By some accounts only one fail safe was left in place when its parachute snagged on a tree branch.

The 1966 – 17 Jan – B-52 crash off the Spanish coast was almost as dangerous. The B52, carrying four bombs – each one worth about 900 hiroshimas, took off from the Seymour Johnson Air Base (see above) and was on a mission in the Mediterranean when it ran into trouble after a failed mid-air refuelling. The plane crashed just outside the village of Palomares in Andalusia and its wreckage was spread over a large area. The four bombs also came down at various points. Three fell on land and two of these suffered conventional non-nuclear explosions spreading radioactive material wily-nily: these were easily recovered, though let’s not get into the question of cancer rates in the area for the next years and all the contaminated soil. The fourth fell at sea and the US sent their submarines in.

The ‘Miracle of Palomares’ (which is one way to look at this almost Spanish Armageddon) had two comic elements to leaven out the near death of millions of Andalusians. First, ‘the water bomb’ was seen entering the sea by a local, Francisco Simó Orts, who helped the US navy in their recovery mission. Wily old FSO, subsequently known in the village as ‘Paco the Bomb’, however, sent in the lawyers claiming salvage rights! The Feds settled out of court. Paco did not, sadly, have the wisdom to buy a house in distant Galicia, and remained among the frighteningly high radiation levels in the area.

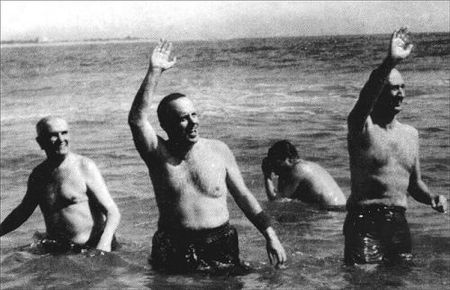

And talking of Galicia, enter the legendary Galician politician Manuel Fraga Iribarne (obit 2012) who was then minister for tourism under Franco. He and the then American ambassador to Spain, Biddle Duke decided to go for a swim at Palomares to convince the world that the incident had passed without serious repercussions for the local environment. The photographs of these two intelligent and powerful men clowning around in the waves (see above) must stand as one of the low points of the Cold War. However, to be fair both made it to a ripe old age: BD died at seventy nine while roller-blading.

These are just four of several nuclear catastrophes 1945-1990: and those, of course, are only the ones that the US government has had the good grace to tell us about. Beach isn’t going to work up a list because he fears that it will be depressingly long. However, if anyone has any good Fraga-like anecdotes: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com It goes without saying that we’ll never hear about the Soviet equivalents.

***

MF writes in with some fascinating comments and corrections. ‘Regarding worries that “Little Boy” would detonate if the Enola Gay crashed, you may rest assured that there were many worries about such an event. There are many built-in safety features to nuclear warheads (even then) which also explains the “miraculous” way that the several (admittedly frightening) mishaps you refer to with nuclear warheads did not result in a detonation. Regarding the flight out of Tinian, you state that “should it accidentally explode most human life on the island, a mere thirty-nine square miles in size, would cease to exist.” I will grant that this type of view of the world-ending nature of nuclear weapons is widely held in the educated, non-nuclear public, but I would like to reply to that statement with a map showing the blast pattern of a “Little Boy” sized warhead in an idealized air drop (much broader effect than a ground-level detonation). There would have been many dead people at the airport, but as for wiping out all life on Tinian, that is overdone. I’d also like to take issue with the idea of the “frighteningly high radiation levels in the area” of Palomares after the B-52 went down. There have been traces of Americium and Plutonium found in a debris trench. There are no known direct effects to health to the people of the area from the low levels of exposure found at that site. There is much controversy over the effects of chronic exposure to low-level radiation levels (start here if you want a piece of radioactive contamination history we are not allowed to talk about amongst right-thinking people). That said, I guess it does come down to what is “frightening” to one person might not be to another. I can see how educated Western elites in non-technical areas who have been told by sincerely righteous people that any radiation exposure is dangerous over and over for decades could generate a significant level of fear. Hopefully this alleviates maybe a little of that fear. Knowledge is power.’ Thanks MF!

19 Oct 2012: Ozzie writes in: I don’t know if this is up to Fraga standards, but I lived for five years in Pocatello, Idaho, which is about 50 miles southwest of the US National Reactor Testing Site. Many local residents worked at “The Site,” and, this being the 70s, there was always worry about whether they would all start to glow in the dark. Whenever concern reached a peak, there was always a comforting announcement made to the effect that “radiation readings at The Site are actually lower than those in Idaho Falls.” Idaho Falls was another town located about 40 miles due east of the site. The prevailing west wind blew directly from the site to Idaho Falls, sending any contaminated dust from the test site to the city. Oh, how we laughed. Thanks Ozzie!

31 Oct 2012: Sleeper writes ‘One of my neighbors when I was growing up had been invalidated out of the Army Air Corps during the war due to rheumatic fever. Since he was from Eastern Washington State he went home and wound up with a job running trucks at Hanford , where a lot of the nuclear material was purified. He said he had been issued a dosimeter for working on the site, and it was checked daily. He worked for a while running a water truck sprinkling water on the roads and lanes in the facility to keep down the dust. He said one day he noticed a bunch of guys in enveloping white suits working at one building, and it was so interesting he made multiple passes at the site, driving round and round the building. When he went in the next day his dosimeter badge was missing, and he was told it had been over-exposed, but he should wait a minute and they would find him another one – and they did, that was all they did about the over-exposure. He found out later he had been circling the main reactor as they were loading it up. Health and safety regulations were a little less stringent then, I’m sure WA Labor and Industries (LNI) would have something to say about that today.’ Thanks Sleeper!