Cartooning the Great War October 8, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback***Dedicated to KR***

Beach wasted a couple of hours this morning thanks to KR who got him interested in online Great War cartoon books. There are the first and second volume of Raemakers’ Cartoon History of the War and perhaps more to Beach’s taste Punch’s History of the War. Can he also advertise this little known American effort that, in past years, he has used with students about an American Division in Italy? It is obscure but fun…

Why bother with such cartoons when you can go and read Graves or Erich Maria Remarque? Well, if history is about reading until we can hear the generations past speaking, looking at cartoons and reading Punch’s facetious poems means flicking through the pages until you can hear the generations past laughing. Beach also suspects that ‘low’ art – though fans of Raemakers might justly get irate here – tells you more about the past because it is nearer to the thoughts of normal men and women. In other words, a burbling Elizabethan dramatist would bring us closer to the seventeenth century than Shakespeare.

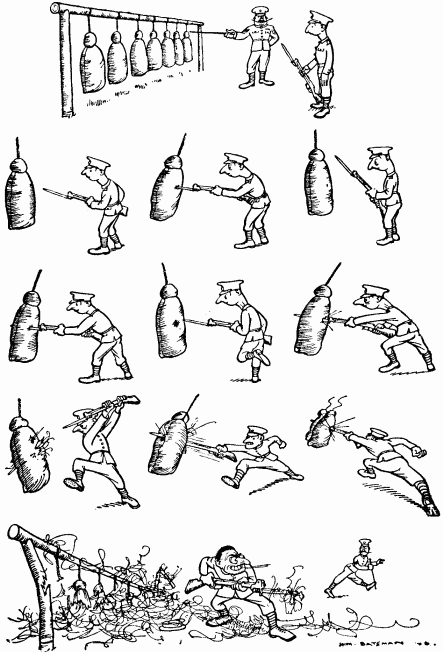

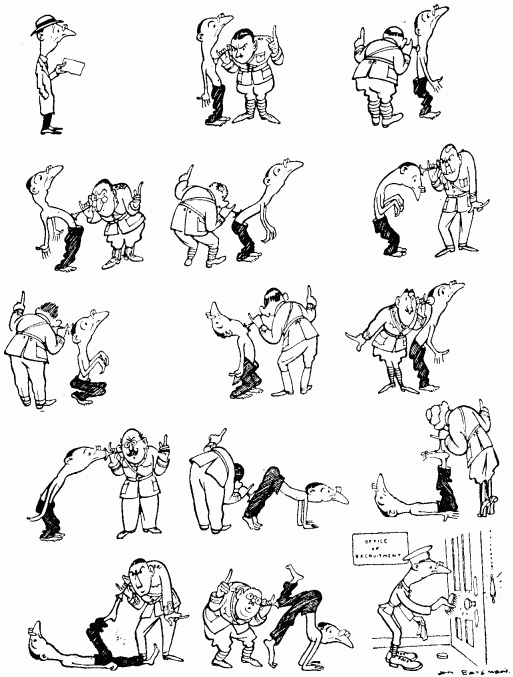

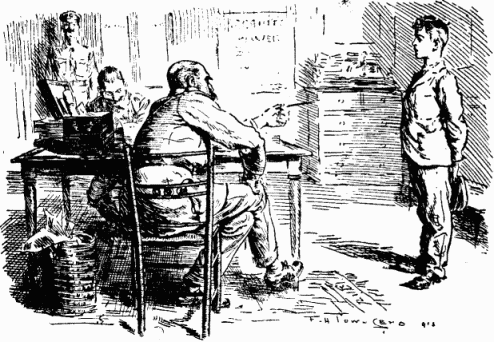

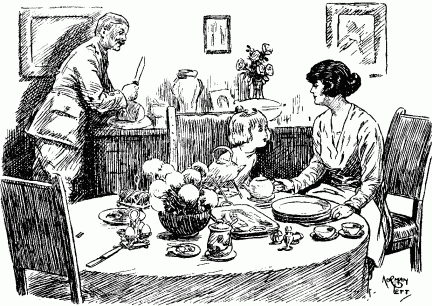

Having said that there is some fantastic draftsmanship and wit here. Beach was particularly impressed by one Punch artist who perfected tableaus of military life: a couple are included here.

A politician visits the soldiers

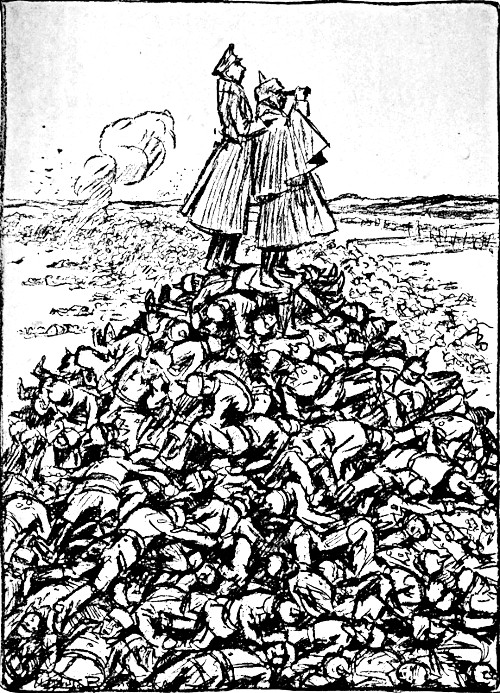

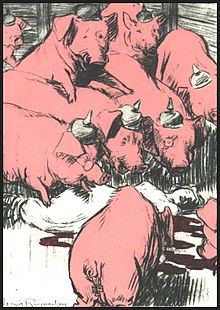

Then Raemakers himself tended towards the darker Dutch humour of his younger days, but there are occasional belly laughs. Beach liked most this one of the German failure at Verdun: ‘We must have a higher pile to see Verdun, Father’.

Here is another excellent Punch cartoon, a thirteen year old trying to get into the war is asked by the recruitment officer: ‘do you know where lying boys go?’ He answers without missing a beat: ‘to the front, sir!’

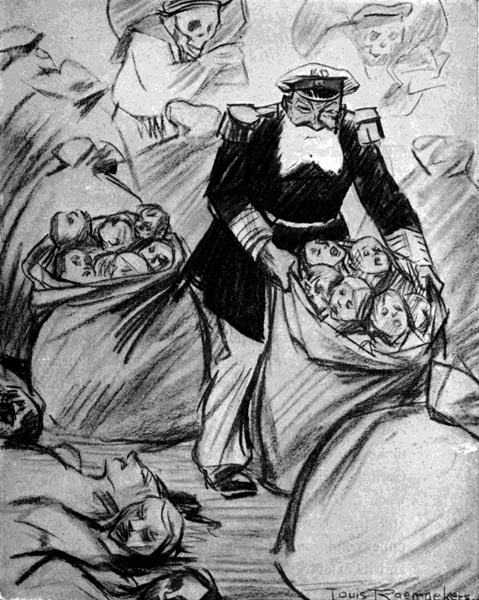

A century has passed and the double standards of these cartoons are strikingly clear. Pro-British Raemakers particularly makes a lot of the execution of Edith Cavell, a British national who saved Allied prisoners in occupied Belgium. The Germans were foolish to execute EC given the damage it did to German prestige, particularly in the United States: but it is difficult to argue at this distance of time that what they did was either illegal or ‘wrong’ given that courageous woman’s actions.

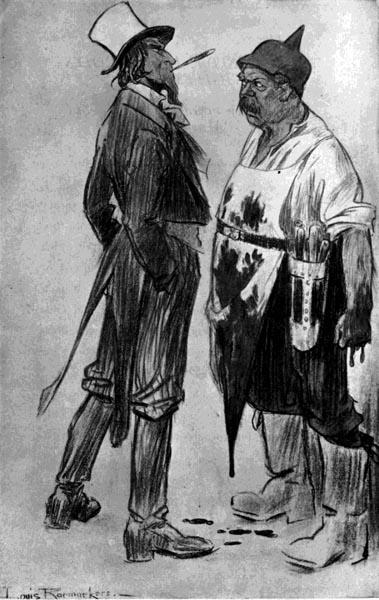

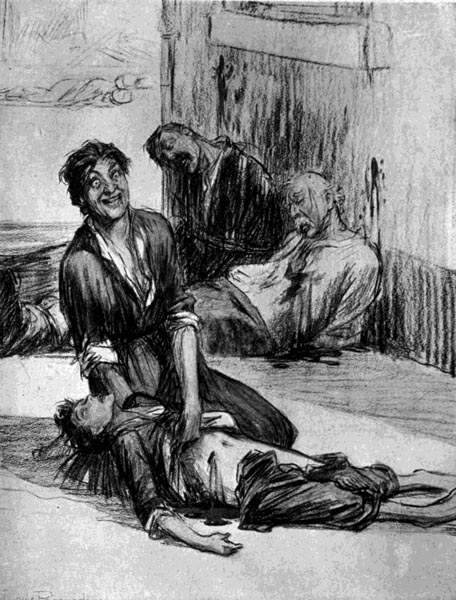

Contrast that then with cartoons of ‘Sir Judas Casement’ (Sir John Casement), an Irish patriot, pictured below, who stupidly involved Germany in his rising against British rule in Ireland. Casement, like Cavell, was saintly: there is the famous comment of the priest who attended him in his last days ‘we should be praying to [Casement] instead of for him’. And in his case there is an argument that the British government was not just foolish but, in legal terms, ‘wrong’ to execute him. Britain certainly erred strategically in its treatment of other Irish rebels in 1916.

Raemakers (and to a much lesser extent Punch) quoted the (often self-incriminating) German press as a backdrop to cartoons or sometimes German greats including Nietzsche. Britain or the US could soon have been vilified on similar grounds if you quoted the nincompoops who were allowed to say their bit in the hate-filled war columns: and as to a British Nietzsche a German propagandist would have had a lot of fun with some of Blake’s aphorisms.

Submarine bags.

But the beastliness of the German army in the occupied territories needs little exaggeration: though, of course, the Allied press and governments did exaggerate. In Belgium the German army had to occupy a territory that was neutral, but whose citizens had a strong sense of national honour. And who knew all too well that the only reason German armies were in the county was because it proved a useful shortcut to France.

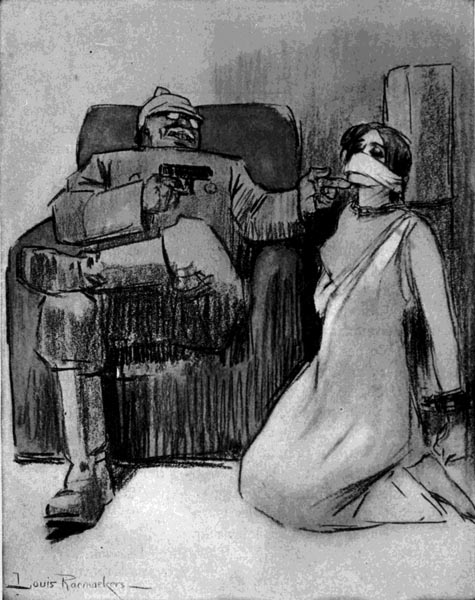

Often in WW1 and WW2 propaganda films the normal rules of violence are suspended as the need to make a point is so much more important than any rules of decency handed down from the Victorians. In cartoons – Beach hopes to look at this in more detail another day – there is a similar willingness to excuse the normal rules of sexual propriety. Take this poor Belgian girl chained before the German monster with her breast exposed. Imagine trying to get that in a British newspaper in 1913!

Beach finishes with this quotation in Raemakers that shows that even in the sturm und drung of 1914 and 1915 Europe remembered its common civilisation: and, far more importantly, in extracts, like this celebrated that civilisation as it went glugging down the plughole.

A corporal named Houston narrated that while he lay wounded on the ground, after the battle of Soissons, he saw a young English soldier lying near him, delirious. A German soldier gave the poor lad water from his flask. The young Englishman, his mind wandering, said, ‘Is it you, mother?’ The German comprehended, and to maintain the illusion, caressed his face with a mother’s soft touch. The poor boy died shortly afterwards and the German soldier, on getting to his feet, was seen to be crying.

CHILD (who has been made much of by father home on leave for the first time for two years): ‘Mummy dear, I like that man you call your husband.’

Any other unusual history books, particularly with cartoons? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

Invisible writes in: For First World War cartoons, you should also look at Brushes & Bayonets, Cartoons, Sketches and Paintings of World War I, Lucinda Gosling, In association with The Illustrated London News Picture Library, 2008. This drawing is “Passed by the Censor”, Edwin Morrow, The Bystander, 16 August 1916 Caption: Officers of the ____Battn. ___Rgt. who took part in a recent advance in ____. Reading from left to right (back row): Lieut___, Lieut___, Sec.-Lieut___, Lieut___, Sec.-Lieut.___. Front Row: Capt.___, Lieut-Col.___, Major___, and Capt.___ Contents: An Illustrators’ War, ‘Over by Christmas’: The Outbreak of War; ‘Who’s for the Trench, Are You, My Laddie?’: Enlistment, Recruitment & Training; Frightfulness: Drawing the Enemy; From Plug Street to Regent Street: Life in the Trenches; Business as Usual: The Home Front; The Blue Pencil: Reporting & Censorship; Carrying On: Women & War; Back to Blighty: Soldiers on Leave; Shoulder to Shoulder: Allies; Venus & Mars: Love & Marriage in Wartime; Up, Up & Away: Land, Sea & Air; ‘The Day’: Victory & Peace.

The Count has this to say: Poor old Kaiser Bill – he managed to start WWI, but today almost nobody remembers him at all, let alone as the classic Supervillain he clearly wanted to be, judging by his constant attempts to dress up as one, skull-and-crossbones and all, while trying to disguise the fact that he had a withered arm. He even retired to a place called Doom! It didn’t work, though – he remains a slightly cartoonish and somewhat inept baddie who wasn’t really in control of events – WWI just sort of happened, more despite than because of him. The fact that the victors allowed him to live out his days in comfortable obscurity and die of old age once he became irrelevant says rather a lot. WWII, on the other hand… During the war, right up until its closing stages, attempts were of course made to portray Hitler & Co. as bumbling cartoon buffoons not unlike the Kaiser. However, when the literally unbelievable horror of what the Nazis had done in the camps finally became all too apparent, the joking had to stop. One artist working for D. C. Thompson later said that he felt horribly ashamed in retrospect for having unwittingly tried to be funny about people capable of such things, even though he couldn’t possibly have known at the time. To see what I’m talking about, here are some images from the wartime Beano of that wacky overweight Italian person Musso the Wop, and, even more unbelievably, by the same artist, and in the Dandy of all places, the slapstick escapades of Adolf Hitler and Hermann Goering! (Readers unaware of these strips miss the real joke underlying Viz Comics’ “Oswald Mosely the Black-Shirted Funny Man”.) Then there is the Great Mike Dash: No post about humour in the First World War is complete without mention of the remarkable and increasingly celebrated Wipers Times, a satirical trench newspaper produced by a group of officers and men from the Sherwood Foresters. They were fighting on the front line, and discovered a working printing machine in a shelled-out print shop, which they thereafter lugged around the trenches with them; the magazine was sometimes actually produced under fire. More than a dozen issues were produced in all. Quite a lot of the humour still stands up, and there are even cartoons, though these had to be engraved in improvised ways. Best of all perhaps are the spoof advertisements:

The WT is an interesting bit of evidence for the persistence of good morale and actual determination to win a war thought worth fighting, and as such it is a useful antidote to the post-hoc war-is-hell version of events that has become the standard narrative of the war. The staff of the Times were even aware of this while the fighting was still going on: We regret to announce that an insidious disease is affecting the Division, and the result is a hurricane of poetry. Subalterns have been seen with a notebook in one hand, and bombs in the other absently walking near the wire in deep communication with the muse…The editor would be obliged if a few of the poets would break into prose as a paper cannot live by “poems” alone. Thanks Mike, Count and Invisible!