Crowds #3: Crowds as Art July 4, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback***Dedicated to Andy the Mad Monk***

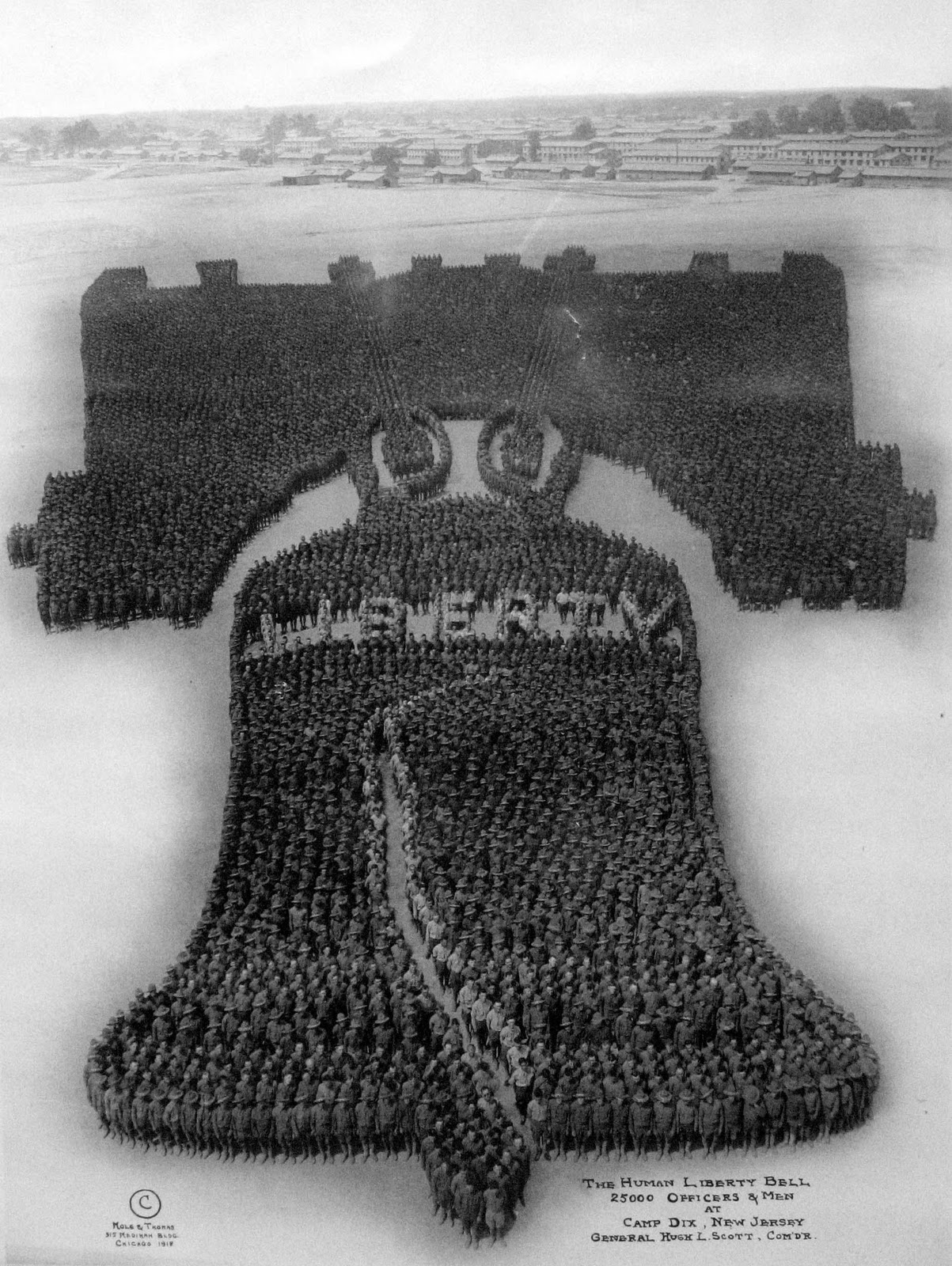

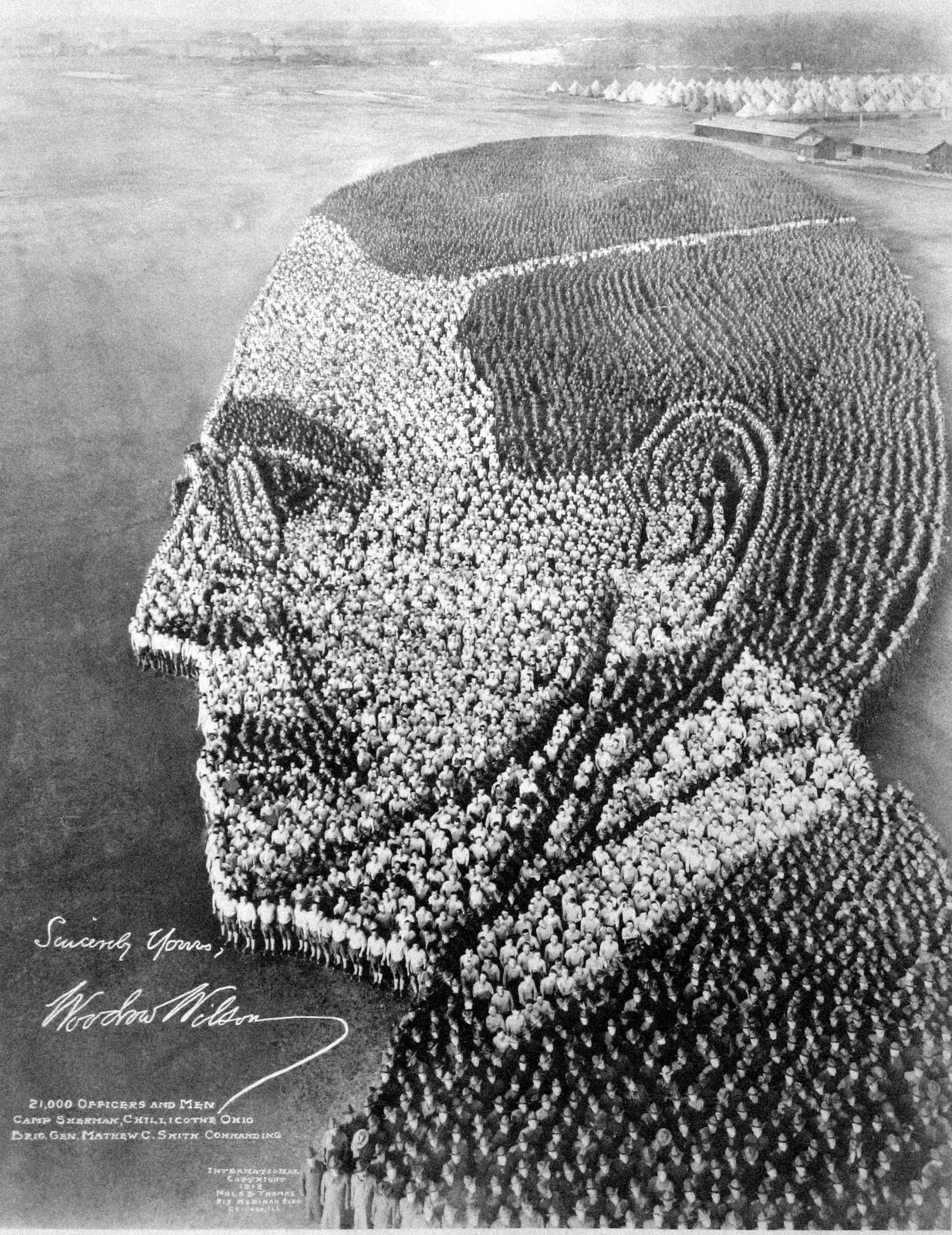

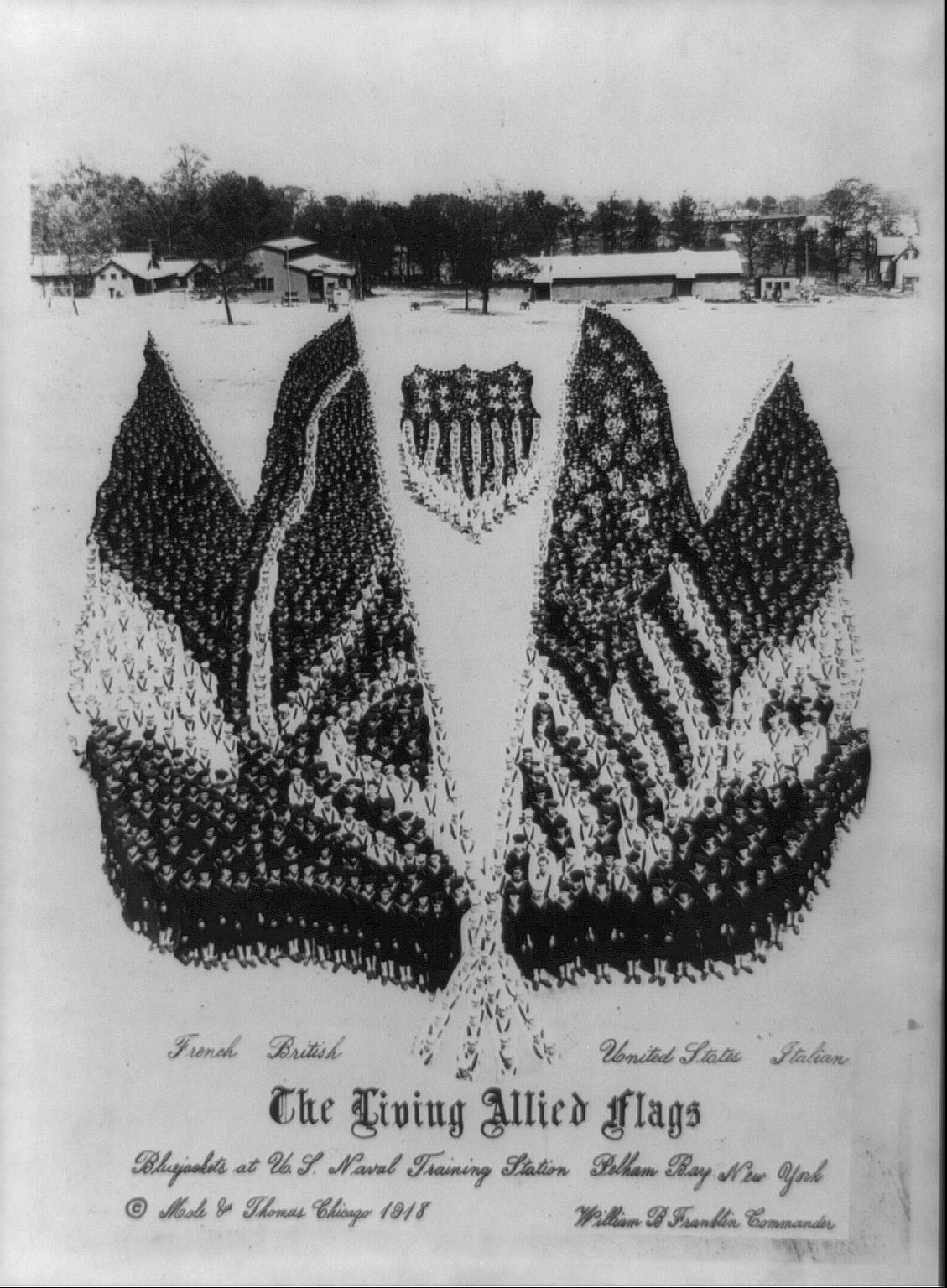

Beach has previously confessed to a thing about crowd photographs: he has put up posts showing August 1914 madness and orators in front of thousands. However, what if the crowd itself is taken out of its random passions and ordered into a work of art? This was the intuition of a British artist Arthur Mole in the First World War who with John D. Thomas travelled around the US to create patriotic pastiches using multitudes as their paintbrushes. The effects are curious, sometimes even pleasing.

How Mole and Thomas, commercial photographers based in Chicago, came up with the idea is not clear. They met in a religious context in Zion Illinois and their first experiments were, allegedly, with church congregations: Beach has only been able to find a 1920 image from Zion though, so he cannot vouch for this.

The famous war images emerged in 1917 and particularly in 1918. How did they pull it off? Well, first, they found a military formation ready to lend themselves to patriotic art. Second, they traced the image they wished to achieve onto a photographic plate. Third, they climbed up onto a high structure, typically a tower made specially for the purpose. Then, fourth, they would begin to get the men (and very often women) into place, we imagine with megaphones: numbers ranged from several hundred to 20,000. By some accounts the whole process could take up to a week and the day of photography must have been incredibly tedious for those being moved around.

Certain images are quite simple, for example, the Liberty Bell, though kudos for getting the crack! But some are extremely complicated: Beach was particularly impressed this morning by looking over Woodrow Wilson’s face. Did it ever go wrong? The image below of the four Allied flags is not a great success.

There is something very ‘modern’ in national symbols being created by the masses, shunted into position by men on towers and shouting sergeant majors. The great American photography historian Louis Kaplan even speaks of a ‘fascistic tendency’. Beach is struck even more by the fact that many of the soldiers in the early pictures would be dead by the time that these photographs appeared in the post-war collections. If we could black out the fatalities, what would that do to the crowd art…

Any other crowd photographs worth publicising? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

5/7/2011: Invisible writes: ‘The photograph of the “living image” of Woodrow Wilson’s head was taken in 1918 at Camp Sherman, Chillicothe, Ohio. 21,000 men were used to make the image. This link gives some of the statistics. This must have been taken only days or weeks before the influenza hit Camp Sherman in late summer/fall. The camp saw the highest death rate of any military training camp in the United States. The camp held 33,044 men when the influenza arrived. Out of 8,000 people infected, nearly 1,200 died. Corpses were taken to a nearby theatre (now The Majestic), stacked in the dressing rooms under the stage, and embalmed on the stage. Luridly, the overwhelmed embalmers pumped blood into the alley behind the theatre, still known today as “Blood Alley.” So, yes, it is possible that many of these soldiers were dead, not in battle, but in their barracks, by the time this photo was made into a postcard.’ Thanks Invisible!