Ecdicius and the Eighteen January 25, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient , trackback

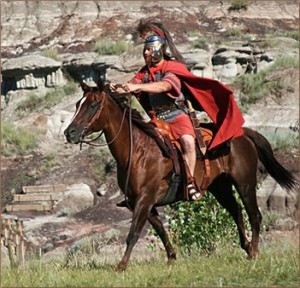

Beachcombing’s recent description of the Roman end times – the grinding to dust of Roman civilisation in the fifth century – got him musing on one of his favourite decline and fall scenes. The following is a letter from Sidonius Apollinaris (obit 489) to his brother-in-law Ecdicius. He is remembering the moment some months or years before when Ecdicius had saved the city of Auvergne, the defence of which was Sidonius’ responsibility: Sidonius was then bishop. This surely is a candidate for one of the most bizarre victories in warfare: a tiny force of cavalry against, allegedly, thousands of barbarians.

Nothing so kindled [the locals] universal regard for you as this, that you first made Romans of them and never allowed them to relapse again. And how should the vision of you ever fade from any patriot’s memory as we saw you in your glory upon that famous day, when a crowd of both sexes and every rank and age lined our half-ruined walls to watch you cross the space between us and the enemy? At midday, and right across the middle of the plain, you brought your little company of eighteen safe through some thousands of the Goths, a feat which posterity will surely deem incredible. At the sight of you, nay, at the very rumour of your name, those seasoned troops were smitten with stupefaction; their captains were so amazed that they never stopped to note how great their own numbers were and yours how small. They drew off their whole force to the brow of a steep hill; they had been besiegers before, but when you appeared they dared not even deploy for action. You cut down some of their bravest, whom gallantry alone had led to defend the rear. You never lost a man in that sharp engagement, and found yourself sole master of an absolutely exposed plain with no more soldiers to back you than you often have guests at your own table.

illud in te affectum principaliter universitatis accendit, quod quos olim Latinos fieri exegeras barbaros deinceps esse vetuisti. non enim potest umquam civicis pectoribus elabi, quem te quantumque nuper omnis aetas ordo sexus e semirutis murorum aggeribus conspicabantur, cum interiectis aequoribus in adversum perambulatis et vix duodeviginti equitum sodalitate comitatus aliquot milia Gothorum non minus die quam campo medio, quod difficile sit posteritas creditura, transisti. ad nominis tui rumorem personaeque conspectum exercitum exercitatissimum stupor obruit ita, ut prae admiratione nescirent duces partis inimicae, quam se multi quamque te pauci comitarentur. subducta est tota protinus acies in supercilium collis abrupti, quae cum prius applicata esset oppugnationi, te viso non est explicata congressui. interea tu caesis quibusque optimis, quos novissimos agmini non ignavia sed audacia fecerat, nullis tuorum certamine ex tanto desideratis solus planitie quam patentissima potiebare, cum tibi non daret tot pugna socios, quot solet mensa convivas.

This is a precious memory from the post-Roman fifth century, the only eyewitness account we have of a Roman force defying the barbarian invaders successfully. And Ecdicius did it with the style that makes Hollywood movies unbelievable.

If there were more sources from that dark century – the most obscure in our era – we might better judge the deeds of similar Roman heroes in Britain and Spain who fought the barbarian waves: like Cu Chulainn on the strand, uselessly but with nifty footwork. Certainly this was the way that legends were made: in the excited imaginations of populations who had despaired at salvation. Read now in many ways the most moving part of Sidonius’ letter, his description of how Ecdicius was greeted in the city he had just saved.

Imagination may better conceive than words describe the procession that streamed out to you as you made your leisurely way towards the city, the greetings, the shouts of applause, the tears of heartfelt joy. One saw you receiving in the press a veritable ovation on this glad return; the courts of your spacious house were crammed with people. Some kissed away the dust of battle from your person, some took from the horses the bridles slimed with foam and blood, some inverted and ranged the sweat-drenched saddles; others undid the flexible cheek-pieces of the helmet you longed to remove, others set about unlacing your greaves. One saw folk counting the notches in swords blunted by much slaughter, or measuring with trembling fingers the holes made in cuirasses by cut or thrust.

hinc iam per otium in urbem reduci quid tibi obviam processerit officiorum plausuum, fletuum gaudiorum magis temptant vota conicere quam verba reserare. siquidem cernere erat refertis capacissimae domus atriis illam ipsam felicissimam stipati reditus tui ovationem, dum alii osculis pulverem tuum rapiunt, alii sanguine ac spumis pinguia frena suscipiunt, alii sellarum equestrium madefacta sudoribus fulcra resupinant, alii de concavo tibi cassidis exituro flexilium lamminarum vincla diffibulant, alii explicandis ocrearum nexibus implicantur, alii hebetatorum caede gladiorum latera dentata pernumerant, alii caesim atque punctim foraminatos circulos loricarum digitis livescentibus metiuntur.

It is tempting to ask whether in Britain the Arthurian legend was not born in scenes like this as one Roman leader or another – an Ambrosius or a Constantine – drove the Saxons back from the hills and returned victorious to Cadbury or another green castrum.

An aside. The account of Ecdicius is also given at third or fourth hand in Gregory of Tours who says that Ecdicius charged with just ten men (rather than 18): like Falstaff’s growing band of ruffians, we have Ecdicius’ shrinking band of partisans.

If we had only Gregory to rely on we would dismiss the account out of hand or rationalise it away. As it is we have the baroque Latin of Sidonius who watched events from the walls of the city and Ecdicius’s success, while remaining inexplicable, is confirmed as fact.

Beach is always on the look out for impossible victories in weird wars: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

28/1/2012: Tacitus from over at Detritus sends some good Sidonius stuff in from his own site. Then RG, an old friend of the blog, writes – vis-à-vis ‘certainly this was the way that legends were made: in the excited imaginations of populations who had despaired at salvation’ – There’s an interesting brief exposition of this theory about heroic myth in MK Joseph’s experimental/SF novel The Hole in the Zero. In one segment, the character Paradine becomes a mythic hero, and finds himself described in a book: ‘Lord Paradine is, in fact, a typical example of the kind of heroic superman almost invariably invented in cultures undergoing a final period of steep decline, as compensation for the experience of cultural overthrow. They are then normally taken over and elaborated in the romance cycles of the succeeding culture’. Thanks Tacitus and RG!!