Escapes, Wives and Cases October 21, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackbackA reflection on escapees. Beachcombing was brought up in the shadow of the Second World War where escape stories were nutrition for a growing boy. Then he made the mistake of reading the Count of Monte Cristo at an impressionable age. Are there any more exciting pages in fiction than Edmond’s fake funeral? Beach can still feel the cold water when the sack hits the ocean.

In any case, in his bulging file of great historical escapes Beach has every imaginable jailbreak from attempts to fly out of the loft to more earthy tunnels and do-or-die running and jumping. And as he has never written on escape material before Beachcombing thought that he would start small with his two favourite examples of being carried to liberty.

First up is Hugo Grotius (obit 1645), founder of international law, who managed to get himself removed from his cell by his jailers, which is certainly adding insult to injury. The following appears in Charles Butler’s Life with some normalisations of spelling. It will soon be realised that the real hero of the piece is not Hugh – whose gift to the world has been of doubtful value – but Mrs Grotius.

[Grotius] beguiled the tedious hours of confinement by study, relieving his mind by varying its objects. Antient and modern literature equally engaged his attention: Sundays he wholly dedicated to prayer and the study of theology. Twenty months of imprisonment thus passed away. His wife now began to devise projects for his liberty. She had observed that he was not so strictly watched as at first; that the guards, who examined the chest used for the conveyance of his books and linen, being accustomed to see nothing in it but books and linen, began to examine them loosely: at length, they permitted the chest to pass without any examination. Upon this, she formed her project for her husband’s release.

She began to carry it into execution by cultivating an intimacy with the wife of the commandant of Gorkum. To her, she lamented Grotius’s immoderate application to study; she informed her that it had made him seriously ill; and that, in consequence of his illness, she had resolved to take all his books from him, and restore them to their owners. She circulated everywhere the account of his illness, and finally declared that it had confined him to his bed. In the mean time, the chest was accommodated to her purpose; and particularly, some holes were bored in it, to let in air. Her maid and the valet of Grotius were entrusted with the secret. The chest was conveyed to Grotius’s apartment. She then revealed her project to him, and, after much entreaty, prevailed on him to get into the chest, and leave her in the prison.

The books, which Grotius borrowed, were usually sent to Gorkum; and the chest, which contained them, passed in a boat, from the prison at Louvestein, to that town. Big with the fate of Grotius, the chest, as soon as he was enclosed in it, was moved into the boat. One of the soldiers, observing that it was uncommonly heavy, insisted on its being opened, and its contents examined; but, by the address of the maid, his scruples were removed, and the chest was lodged in the boat. The passage from Louvestein to Gorkum took a considerable time. The length of the chest did not exceed three feet and a half. At length, it reached Gorkum: it was intended that it should be deposited at the house of David Bazelaer, an Arminian friend of Grotius, who resided at Gorkum. But, when the boat reached the shore, a difficulty arose, how the chest was to be conveyed from the spot, upon which it was to be landed, to Bazelaer’s house. This difficulty was removed by the maid’s presence of mind; she told the bystanders, that the chest contained glass, and that it must be moved with particular care. Two chairmen were soon found, and they carefully moved it on a horse-chair to the appointed place.

His wife waited for her husband’s escape to be confirmed and then she informed the guards. She was imprisoned but set free days later and travelled to HG in Paris. As Butler writes: ‘It is impossible to think without pleasure of the meeting of Grotius and his heroic wife.’

Typically enough two separate museums claim to have the book chest in question: one in Delft and one in Amsterdam. Then on the subject of cobblers, Beach should note that his favourite line from the escape is not recorded in the sources he has checked. One of the guards carrying the chest is said to have felt the box and to have said that it was so heavy that there must be an Arminian in it. To which Mrs G replied with admirable promptitude that there were Arminian books therein. Let’s hope it is true.

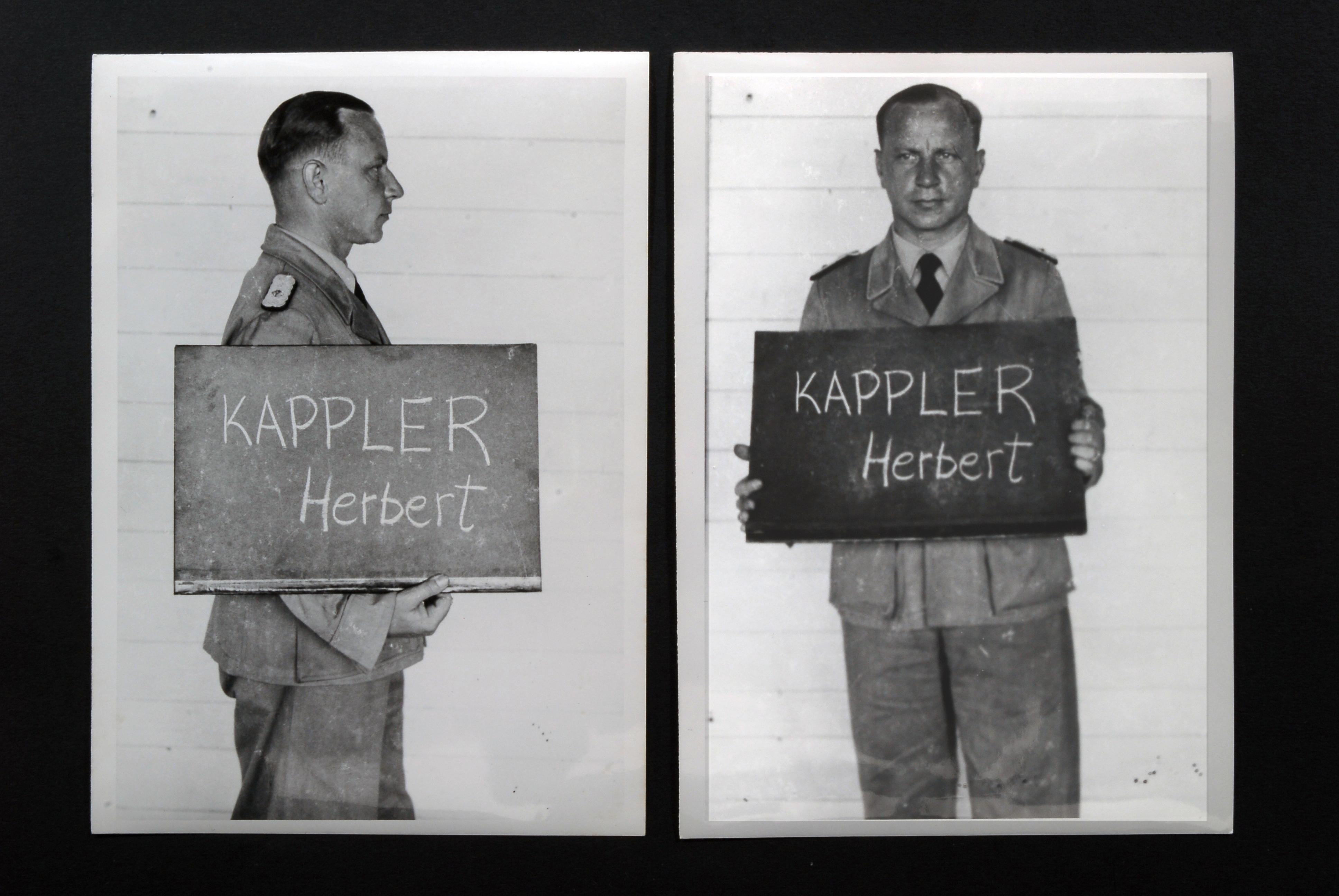

A second carrying escape took place in 1977 and also involved a resourceful wife. This time though, instead of a proto international lawyer we have, Herbert Kappler, a much bloodied SS Nazi, responsible for the death of hundreds of Romans in 1943 and 1944. Grotius studied in prison, Kappler bred goldfish and played the violin.

Kappler had been sentenced to life imprisonment after the war – a lenient sentence given the appalling suffering that he and his brethren had caused. However, in 1975 he was diagnosed with colon cancer and he was moved to a Roman prison hospital (Celio).

Enter now Mrs K.

The Mrs K. in question was not the original (who had got a divorce after the war) but one Anneliese Wenger Walther, a daughter of a WW2 German captain who had enjoyed a long correspondence with Kappler before travelling to Italy and marrying him in 1972. Anneliese was a professional nurse and once Kappler was in secure quarters in the prison hospital the Italians allowed her to look after his every need.

Anneliese proved a remarkable woman. Despairing at the refusal of the Italian government to release her husband who was, already in 1976, given few months to live, she decided to act herself. She brought a large suitcase into the room and carried her cancer-eaten husband out in it, allegedly with the help of the carabinieri. Recent revelations suggest that she was also assisted by a number of friends from German-speaking Italy, and that the original plan had been to fly Kappler to Germany. After a plane malfunction though he had had to be driven.

Not the least interesting part of this story came in the diplomatic fire storm that followed. Italy naturally asked for the prisoner and his colon back. The Germans, a close Italian ally at that date, refused with the striking argument that as a prisoner of war Kappler had exercised his right to escape!

No arguing with that. Kappler died in 1978.

Beach is on the look out for original historical escapes: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

23 Oct 2011: Best email on this from Tim: ‘WWII POW lore is a side interest of mine. Did you know that in one instance Allied fliers had to evade Japanese, German and Russian captivity, and made their way home from the mission by going around the world? And there was vodka involved. One crew of the Doolittle raid decided to disobey the orders to land in China. (or had secret instructions per some accounts). They touched down in Vladovostock and were interned by the Russians. Russia was an ally with respect to Germany, but neutral regards Japan. Eventually they were shipped east to the Caucus mountains….just in time to have to pack up and move as the German offensive on (and past) Stalingrad was threatening them. Finally they were sent to a camp near the border with Iran,then under British control. One day the NKVD guards pretty much pointed them in the right direction then looked elsewhere and whistled while the five Americans scampered to freedom!’ What a story! Thanks Tim!

27/10/11: Plaid Cymru writes in – ‘What about some glorious failures. Gruffudd ap Llewyllyn lost his life while trying to climb out of the tower of London, according to Matthew Paris, after having made a roper of tapestries and sheets. Ouch!‘ Thanks PC