Vivoo in Naples September 8, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackBeach has spent a few minutes this evening reading through the Economist’s exposé of modern Italy entitled: Oh for a new Risorgimento, and this got him thinking of his own favourite Risorgimento moment and a first-rank wibt (wish I’d been there) scene.

The year is 1848 and mobs around Europe from Tipperary to Prague are causing trouble out in the streets. For those who like their history deep baked, there is a suspicion that this, along with Napoleon’s birth, the French Revolution, Lenin passing into Russia and baby boomers growing their hair too long in 1968 was one of those moments when the world was shaken off the safe tracks that had been so carefully laid down in the Renaissance.

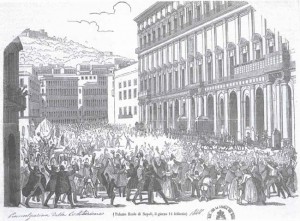

But if you have to have mob violence where better to see it in action than Naples: the Calcutta of Europe, a magical, royal, decrepit place? Even today if you visit the city at New Year, as neighbours aim fireworks at each other’s balconies and hurl champagne bottles out of windows, you get a sense of how wild the city’s underside is. Naples though has long had a reputation for giving over the power to the mobs, who came down their narrow stairwells with knives between their teeth.

And so it was hardly surprising that when 1848 came and news of uprisings elsewhere arrived in the city the poor walked out for one of their occasional orgies of violence. But it was not just the poor. There were also curious foreigners and the braver members of the Neapolitan middle classes among them Luigi Settembrini (obit 1876).

Settembrini had been born in the city, but unusually for Naples he was an Italian patriot and had despaired at the way Naples showed a complete lack of interest in the unity of the peninsula: reading the Economist’s report the ‘people’ may have been right, but anyway…

1848, however, was a special year for Italy: as unrest spread through what was to become Italia, everywhere, even in proud Venice (that definitely would have been better off on its own) the people took up the cry Viva l’Italia and eventually this slogan reached Naples. This passage in Settembrini’s memoirs evidently represents one of the most intensely lived moments in his long life.

The lower orders and the young, not knowing what they ought to say, and wanting to shout and perhaps mock, repeated ‘Vivoo’, a meaningless sound, because to them the change was meaningless. But words cannot indicate the emotions we felt at hearing many humble people shouting ‘Viva l’Italia! We are Italians!’

That word Italy, which had at first been uttered by a few and in secret, which had been heard by only a handful, and which had been the last sacred word uttered by so many honourable men as they died – to hear it now uttered and shouted by the people made me feel a tingling run down my spine and through my body, and constrained me to tears…

Settembrini happily survived to see Rome and Venice brought into the Regno and, even better, died before it was clear what a mess Garibaldi and Cavour’s successors had made of the new country. But his description of Naples on that extraordinary night was partial. One British diplomat describes how many in the crowds milling through the boulevards were confused as to what the word ‘Italy’ meant: Settembrini only hints at this with his ‘vivoo’.

Beachcombing is always looking out for striking historical moments: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com