The Hare that Killed a Hundred Thousand July 25, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient , trackback

Beachcombing was much struck by some of the comments concerning his Amazon article about the terrifying warrior women of Benin. Several of the examples given by readers were not though of warrior women per se: but of women war-leaders, which is a fascinating phenomenon and one which is certainly more common. Think Joan of Arc, think the terrifying Caterina Sforza, think the Trung sisters in Vietnam… Joan is the only one on this list who would have actually used a weapon: the others gave instructions from behind the barricades and perhaps helped torture any prisoners after the battle was over, but they were not warriors as such. All this led in Beach’s mind to WIBT (wish I’d been there) moment from early British history involving a hare and a very angry lady: a moment that is only a hint in an early Roman text – a dozen words of Greek – but one that has always haunted him.

In 61 AD the Iceni, a British-Celtic tribe from what is today Norfolk reacted in fury to Roman occupation tactics. Their king, Prasutagus, a Roman client had recently died and the Roman government had humiliated the royal family by beating Prasutagus’s wife Boudica and dishonouring their daughters. Boudica though was not going to take this and the clans rose in sympathy.

The person who was chiefly instrumental in rousing the natives and persuading them to fight the Romans, the person who was thought worthy to be their leader and who directed the conduct of the entire war, was Boudica, a British woman of the royal family and possessed of greater intelligence than often belongs to women. This woman assembled her army, to the number of some 120,000, and then ascended a tribunal which had been constructed of earth in the Roman fashion. In stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce, and her voice was harsh; a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was a large golden necklace; and she wore a tunic of different colours over which a thick mantle was fastened with a brooch. This was her invariable attire. She now grasped a spear to aid her in terrifying all beholders and spoke as follows..

This passage is the run up to a set piece speech by the British leader and appears in Cassius Dio. The speech itself will certainly be – in the way of ancient texts – a mish-mash of Roman prejudices and conceits with no historical basis: though the idea of a journalist from Reuters Rome transcribing the discourse in short-hand as Boudica spoke is enjoyable. But CD has access to some genuine information. The description is reminiscent of an aristocratic British woman of this period and more interesting still is a detail that rounds off his account.

When [Boudica] had finished speaking, she employed a species of divination, letting a hare escape from the fold of her dress; and since it ran on what they considered the auspicious side, the whole multitude shouted with pleasure.’

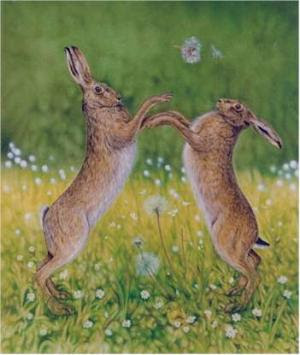

The hare ran in such a way that the Britons were persuaded that their divinity favoured revolt. There is no basis for this in Roman practice and so the presumption is that this is a genuine detail from the Celtic marches of the Empire. After all, the hare did have a special mythological role among the British – perhaps because it fights? Caesar claimed that it was, along with the goose, a taboo animal for the British. And one of the most important works on Celtic mythology on the market today, Green, The Gods of the Celts, 174, weaves archaeological evidence into this.

‘Apart from associations with hunters… hares may be associated with some interesting evidence for ritual. Hare-bones appear in pits, for example at Ewell, Surrey, and at the Thistleton Dyer shrine a bronze hare was found in a pit, each with a small piece of hare-fur. Most interesting in its complexity is the ritual deposit at Winterbourne Kingston, Dorset where an eighty-five foot deep shaft contained brooches, coins, bones, a Purbeck marble vase and a bronze hare; nearby was a ritual structure demarcated by eight burnt tiles in the centre of which were a knife and a small conical sarsen.’

Beachcombing thanks Cassius humbly then for this precious glimpse from one of the bloodiest revolts in the Empire’s history. He hears the carnyx in the Broads bringing the warriors to their meeting. He watches the terrifying woman in the glade and glimpses the hare running from out between her legs as she squats. He sees the animal lolloping, say, to the left through the long grass as the clans roar their appreciation, every jump forward another ten thousand Romans dead: for ‘two cities were sacked, eighty thousand of the Romans and of their allies perished, and the island was lost to Rome’ at least for a season, then there were the deaths among Boudica’s allies and her lost tomb: one of the great mysteries of British archaeology.

It is interesting to speculate why women like B. reach positions of military power. Is it just chance? Is it the arrival of a remarkable individual? Or is it a society in crisis trying to reconfigure itself?

Perhaps women are a neutral choice for leaders in a tribal federation? In Celtic terms certainly a matriarch – the incarnation of Sovereignty no less – from East Anglia or the Pennines might have been a more appetizing unifier of disparate peoples than a man who was partisan and the head of a single tribe. Was Boudica or her northern cousin Cartimandua seen as being above it all?

Any thoughts on the ‘why’ of women war leaders or further examples of the same: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

23 Nov 2011: Sy sends in this ‘The romantic glen was in the first instance the retreat of a beautiful Irish maiden, Monacella (in Welsh, Melangell), who had fled from her father’s court rather than wed a noble to whom he had promised her hand, that here she might alone serve God and the spotless virgin. Brochwell Yscythrog, Prince of Powys, being one day hare-hunting in the locality, pursued his game till he came to a thicket, where to his amazement he found a lady of surpassing beauty, with the hare he was chasing safely sheltered beneath her robe. Notwithstanding all the efforts of the sportsman to make them seize their prey, the dogs had retired to a distance, howling as though in fear, and even when the huntsman essayed to blow his horn, it stuck to his lips. The Prince, learning the lady’s story, right royally assigned to her the spot as a sanctuary for ever to all who fled there. It afterwards became a safe asylum for the oppressed, and an institution for the training of female devotees. But how long it so continued cannot be said. Monacella’s hard bed used to be shown in the cleft of a neighbouring rock, while her tomb was in a little oratory adjoining the church. In the church is to be found carved woodwork, which doubtless once formed part of the roodloft, representing the legend of Saint Melangell. The protection afforded by the saint to the hare gave such animals the name of Wyn Melangell – St. Monacella’s lambs – and the superstition was so fully credited that no person would kill a hare in the parish, while it was also believed that if anyone cried ‘God and St. Monacella be with thee’ after a hunted hare, it would surely escape.’ Thanks SY