The Dauphin’s Heart June 11, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackback

Beachcombing is for ever rabbiting on (and on) about how time destroys memory, how everything we are told is unreliable. But the untrustworthiness of history applies not only to memory but also to objects. And what better example of this than the heart of the last dauphin, poor Louis XVII.

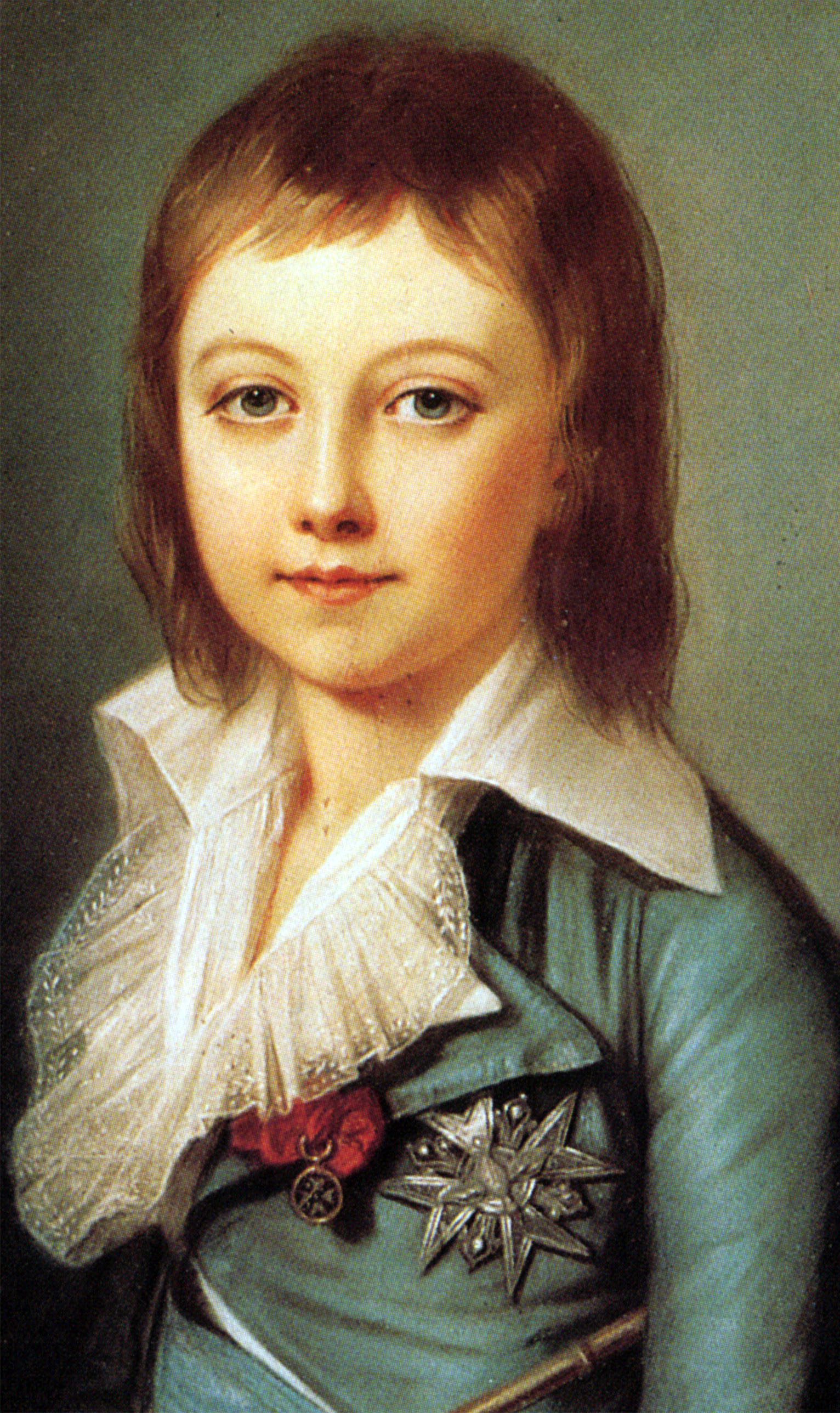

Louis was collateral damage in the French revolution. He was seven when the sans-culottes decided to end civilisation: ‘the glory of Europe is extinguished for ever’. And he was ten when he died, in 1795, a lone prisoner in the Temple Tower in Paris, his mother and father having already gone to pay for their dynastic blood on the steps of Monsieur Guillotine.

1) At the autopsy in 1795 the doctor in attendance, Pelletan, decided (as you do) to take Louis’ heart as a souvenir. Pelletan squirreled the heart away, unseen by the other doctors, and stored it in a crystal cup in liquid on a bookshelf.

2) In 1810 Pelletan noticed that the heart was missing and decided that the thief was a student of his, a Dr Tillus: in a dangerous Republican age Pelletan had told only Tillus the story of the heart. Pellatan tracked down Tillus who had just died of tuberculosis and convinced Tillus’ wife to give the heart up.

3) In 1828 the heart was handed over to the Archbishop of Paris in a casket with the crystal cup and various papers describing its history: the Archbishop had hoped to get it back to the royal family. But in 1830 in riots in the capital – revolutions teach bad habits – a group of ne’er-do-wells got into the Archbishop’s building and two looters, not knowing what was inside, fought over the casket. In the fight a sabre blow smashed the crystal cup and the heart disappeared. The heart was later found on the floor of the room.

4) In 1895 the heart was handed over to the Bourbon claimant to the throne, Don Carlos, with whom it travelled to Frohsdorf in Austria, where it sat next to Marie Antoinette’s bloodstained scarf from the day of her guillotining: ‘I thought that ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards…’ Mother and son were reunited.

5) In 1942 the heart was taken to Italy by Don Carlos’ daughter.

6) Then in 1975 the heart was handed over to the royal relic collection at Saint Denis where it remains to this day.

The heart enjoyed six different stops in its journey through Europe. But, knowing the conjuring trick that is history, can we be sure that the heart that was handed over to Saint Denis was really the heart that Pelletan pulled out of the Dauphin in 1795?

There are several problems. First, did Pelletan tell the truth or did he just invent a relic? Second, did Mme Tillus give back the correct heart or had she procured an alternative? Third, the Archbishop had at least two hearts in his offices. Are we sure that Louis’s guardians got their hands on the right one? Fourth, there are then the years of travel outside France when the heart was stored with relics and confusion between similar relics is possible: particularly in wartime when objects are being moved quickly. There is also, fifth, the very confusing fact that a letter dating to 1885 claims that Louis’ heart was at Frohsdorf already in that year: did two hearts get mixed up there?

There is a happy ending of sorts. In 1998 a DNA test was carried out on the heart and it was established that the heart shared DNA with Maria-Antoinette. This surely shows that the ‘chain of custody’, however, bizarre had worked. Pelletan had taken the heart from the Dauphin and that heart now resides at Saint Denis.

Only, perhaps it doesn’t…

When the heart was kept in the Archbishop’s offices it was, allegedly, kept next to the heart of Louis’ elder brother, Louis Joseph, who also died in childhood. It would have been very easy in the confusion for someone to pick up the wrong heart and, of course, the DNA would match.

True there is an account that Louis Joseph’s heart had been one of forty four royal hearts (!) that in 1793 had been grabbed by a rioting mob – another… – at the Val de Grâce, thrown into a wheelbarrow and then all burnt… But this too is contested.

Finally, there is the allegation that the boy who died in 1795 was not the real Louis XVII, a ‘fact’ that muddies the water just a little bit more.

All this begs a question: if historians cannot keep track of a simple human organ over two hundred years what hope can professionals of the past have of understanding why the First World War began or why the Roman Empire fell?

Consider too this. There is only one source that tells us that the two princes’ hearts were kept in close proximity 1828-1830, if that source had not survived no one would have the courage to suggest such a bizarre coincidence and the DNA test would be incontestable. How often are cast-iron facts in history, anything but?

Later this week – if he finds a new aupair and gets rid of the mice – Beachcombing will turn to the day when a prize English eccentric William Buckland ate Louis XIV’s heart: in the meantime any heart stories… drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

Invisible writes in approvingly: ‘This post was one of your best – history, mystery, and suspense with a surprise ending. However, I don’t think we can compare keeping track of this human organ, which had a very chequered career, with being able to ascertain the cause of World War I or why the Roman Empire fell. It is amazing that the Dauphin’s Heart survived at all, let alone that we have a paper trail documenting its progress. There are objects at auction that have a lesser provenance. The bigger questions of why nations go to war or why empires fall cannot be so simply charted. How much your post today reminded me of “Lost Hearts”, the M.R. James ghost story about an occultist ingesting the hearts of the young in his quest for enlightenment! But it reminded me even more of the lengthy history of incorrupt (and mystical) hearts in the lives of the Saints of the Catholic church. I was going to list some of them, but this chapter (conveniently posted online although I do have the book) summarises many of the key elements: Transverberation: the piercing of the heart as by a fiery spear usually described as a pain of unbearable sweetness. The statue of St. Teresa in ecstasy by Bernini is a good illustration. The scar of the piercing is usually found in the heart after death. Symbols of the Passion: These are found impressed in the cardiac tissue after death. Several hearts showing the instruments are on display throughout Europe. Clare of Montefalco seemed to have the most detailed example. Hearts enlarged and inflamed and beating in strange ways. Also exuding mystical oils and sweet scents and being found incorrupt. And, weirdest of all, the exchange of hearts, where Christ gives the visionary His own heart for hers/his. It was fairly common in the Middle Ages to bury the heart and the entrails of royalty apart from the body (see The Royal Funeral Ceremony in Renaissance France by Ralph E. Giesey and ‘Heart Burial in Medieval and early Post-Medieval Central Europe’ in Body Parts and Bodies Whole from Studies in Funerary Archaeology 5, edited by Katharina Rebay-Salisbury et al). This probably began as a measure to prevent unpleasant decomposition incidents, but since royal blood/tissue was sacred, one could equate the royal bits with saints’ relics. Churches were honored to received the bowels and heart of royalty. There was also a practical element. While bones could be boiled and bodies carried in casks of spirit, it was easier to embalm and carry a heart if someone of importance died overseas. It was not until the late 18th-early 19th c. that people began to think of heart burial in that overwrought way as romantic and sentimental–as in the case of Trelawny supposedly snatching Shelley’s heart from the pyre. Bury my heart at Wounded Knee. Or, sordidly, the story that Thomas Hardy’s heart, slated for burial in Wessex, might have been eaten by a cat. There are rumors that a pig’s heart was substituted.’ As always, thanks Invisible!