A Book about Spitting April 28, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Actualite, Contemporary , trackback

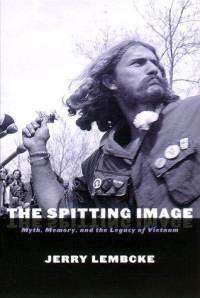

Jerry Lembcke, The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam (New York University Press 1998)

Beachcombing was never going to let a book about spitting in history pass him by. And so when he heard that Jerry Lembcke had given over two hundred pages to the subject, more particularly to the question of Vietnam vets being spat upon, there was nothing, but nothing that was going to keep him away.

Essentially the author has convinced himself that the popular motif of a Vietnam veteran returning from the war and being spat upon by angry hippies or Quaker grannies is a myth.

If this were true then it would be a fascinating example of how we rewrite and distort our pasts and not at all surprising given the general perversion of humanity and the fallibility of memory – themes often visited in these pages.

But how do you go about proving a negative?

This is JL’s problem and he does it in two ways: first by showing friendly – or at least respectful – relations between the anti-war movement and soldiers; and, second, by pointing to the mythic and formulaic nature of the spitting stories that do circulate.

Does he succeed?

Beachcombing was convinced but JL badly hamstrings his own analysis by politicising it.

For him the guilty party is Richard Nixon and co who, in an attempt to shore up support, blamed the anti-war movement for taking support away from ‘our boys’.

Myths stick though because they are needed not because men in power give orders. If this spitting myth circulated and was successful then it was because it told an important truth about the way American society saw Vietnam veterans and the way Vietnam veterans saw themselves.

So why does the author drive past this crucial point?

Arguably because he won’t look some uncomfortable facts about war and democracy in the face.

From Sesame Street onwards we are taught not to kill. Yet, when soldiers are sent out to fight for their country they also necessarily kill for their country: ‘men fought like beasts and hideous things were done’. ‘The deal’ states that society will absolve them when they return – the blood will be washed from their hands and there will be ticker-tape parades.

The great difficulty for a democracy in fighting a war is the danger that a substantial minority will disagree with that war: particularly in the post war period in the shade of Nuremberg, where soldiers are legally responsible for their own actions, orders or no orders.

In criticising a war before war is prosecuted an anti-war faction will unquestionably be carrying out their patriotic duty. However, in continuing to criticise the war once that war has begun – as they are perhaps honour-bound to do – they will also prevent or make more difficult the absolution of those who fight.

In terms of Vietnam, as soon as protestors began to call the commander in chief, LBJ, a baby killer (‘how many kids…’ etc) then they were, in effect, calling US servicemen baby killers as well (as, sadly, in some cases they were). Beachcombing is no fan of the odious Richard Nixon, but he was, at least on one level, right – anti-war activities necessarily hurt ‘our boys’ in the front line, and made their integration after they had returned more difficult.

Whether that means that anti-war protestors were wrong to protest is, of course, another matter: but they certainly had weighty responsibilities both in terms of the victims of the war overseas and in terms of their own fellow citizens in uniform.

For Beachcombing the most productive part of JL’s book was the comparison with spitting stories from other cultures including the German Dolchstosslegende after the First World War – it would have been interesting to bring in too the legend (if that is what it is) of the ‘mutilated victory’ in Italy.

Also interesting are the specifics of the spitting myth – why, for example, is it almost always women who spat on soldiers?

In a chapter entitled ‘Women, Wetness and Warrior Dreams’, JL calls Freud, myth and vaginal fluid into the witness box to explain why women attacked men in the national imagination.

Of course, there is a much simpler explanation. Women can’t be hit! If a ‘long-haired communist’ spits on a returning vet then the vet has to explain why he didn’t pound said long-hair to bits. If a woman is the attacker then the story remains simpler and the impotence of the soldier – the whole point of the myth – is emphasised.

Beachcombing is always on the look out for unusual history books: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

30 April 2011: Author, Jerry Lembcke was straight onto Beachcombing through a nifty little thing called Google Alert: ‘Your explanation for why its is women, not men, who are imagined to be spitters is plausible except that ANY altercations between uniformed personnel and civilians was strictly forbidden and threatened to be severally punished. So the fantasy (that hear often) that ‘if that hippy creep had spat on me, a trained killer 36 hours out of the jungle, I would have smashed his face in . . .’) is just that, a fantasy. And re your observation that protesters did demoralize troops fighting in Vietnam (again, plausible) the survey data reported by VA (and cited in my book) just doesn’t support that.‘ Clearly the best thing that readers can do is to buy Jerry’s stimulating book for themselves and make up their own minds. Beach would counter that (i) the fact of soldier not being able to hit civilians might be a legal reality, but need hardly be attended to by myth and that (ii) it is not so much a question of demoralising troops as delegitimizing what they are doing, something that might not be perceived as a form of demoralisation. While Beachcombing is on the subject he should note that Jerry has recently published another book: Hanoi Jane: War, Sex and Fantasies of Betrayal (UMass Press 2010) that is on Beach’s to read list. Patrick over at the Anomalist writes in with another strange title closer to spitting than to Vietnam: Swallow: Foreign Bodies, Their Ingestion, Inspiration, and the Curious Doctor Who Extracted Them by Mary Cappello, another one for the to read list. Finally, there has been an off site discussion on the post on the question of whether there was or was not spitting post Vietnam. Beach would gladly put any veterans’ stories up here too. Was the myth, in fact, a reality? Only first-person accounts though…Thanks to Jerry and Patrick!!