Atlantean ‘Flying Boats’ February 7, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Modern , trackbackBeachcombing sometimes likes to jot down contents lists for books that he will never write: a further rather melancholy contribution to his Invisible Library collection. He has recently been playing around with Old Atlantis: A Miscellany of Atlantean Madness. The work would have three parts: a bibliography of every book every written on the lost Continent – this list would be intimidating and long and is the main reason that Beachcombing will never write the thing. The second part would be a handlist of theorised locations for Atlantis: from Australia to Mars (really…). Then the last and final part would be a collection of Atlantean sources: ranging from the pre-Platonic tradition (such as it is), through Plato, Proclus and on to the first Atlantean insanities of the early modern period all with – when necessary – facing translation. And with which source would Beachcombing end his tour of Plato’s wet dream? Copyright laws and colour have helped him narrow his choice down to the Atlantean Airships of William Scott-Elliot first described in The Story of Atlantis (1909).

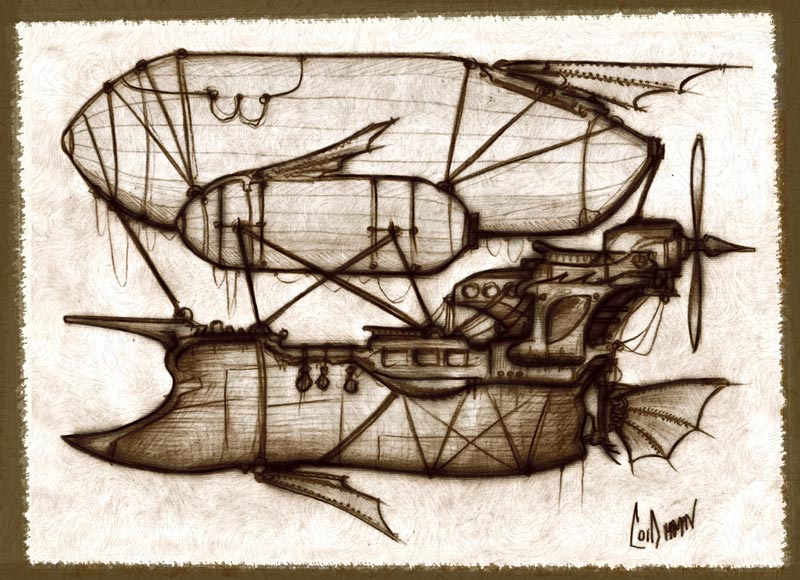

The material of which the air-boats [on Atlantis] were constructed was either wood or metal. The earlier ones were built of wood-the boards used being exceedingly thin, but the injection of some substance which did not add materially to the weight, while it gave leather-like toughness, provided the necessary combination of lightness and strength. When metal was used it was generally an alloy – two white-coloured metals and one red one entering into its composition. The resultant was white-coloured, like aluminium, and even lighter in weight. Over the rough framework of the air-boat was extended a large sheet of this metal, which was then beaten into shape, and electrically welded where necessary. But whether built of metal or wood their outside surface was apparently seamless and perfectly smooth, and they shone in the dark as if coated with luminous paint. In shape they were boat-like, but they were invariably decked over, for when at full speed it could not have been convenient, even if safe, for any on board to remain on the upper deck. Their propelling and steering gear could be brought into use at either end.

The Atlantean air-boats were not large: Numbers were constructed for only two, some allowed for six or eight passengers. In the later days when war and strife had brought the Golden Age to an end, battle ships that could navigate the air had to a great extent replaced the battle ships at sea – having naturally proved far more powerful engines of destruction. These were constructed to carry as many as fifty, and in some cases even up to a hundred fighting men.

Now, of course, the question is where, in the name of Poseidon, did William Scott-Elliott get this information from? After all, most modern Atlanteans are arguing about which of half a million underwater hill-sides are the ‘true’ Atlantis. They make no assumptions about the colour of vehicles that used to traverse the lost Continent, and they certainly do not write about two-man dirigibles.

The answer is that WS-E was an adept of Helen Blavatsky and so he used ‘clairvoyance’ as he called it, which he rather conventionally situated in the Atlantic. His remote viewings took him to specific moments so, for example, while describing the energy sources of these floating ships – something tedious to do with vril – he relied on his observations for a visit to ‘an air-boat in which on one occasion three ambassadors from the king who ruled over the northern part of Poseidonis made the journey to the court of the southern kingdom.’

What an embarrassment of details! The city of Poseidonis, the southern kingdom… We even learn that the generator was a ‘strong metal chest’.

Beachcombing is reminded of an earlier post in which he described the writing methods of a fine English historical novelist, Elizabeth Chadwick and her friend Alison King, who explore together the Middle Ages using a similar method: AK acts as a ‘medium’.

In the worst case scenario these are two perfectly sincere but deluded people, stretching and training up their imaginations. In the best case scenario, they have a key for the locked door of the past: ‘down the path we never opened, into the rose garden’.

Beachcombing is a hoary old cynic and just cannot bring himself to believe in that key: however, much the was-there-really-a-king-Arthur? part of him would like to. He’s inclined then to go for the worst case scenario.

But whereas the worst case scenario for our English novelist means better books for all, for William Scott-Elliot it is all far less appetising. What we have are pages and pages of Atlantean history that bear an uncanny resemblance to the ravings of Helen Blavatsky with her racialist and rather unpleasant assumptions about humanity. An eccentric Atlantis-fixated Episcopalian Vicar c. 1910, say, would have given us some racy science fiction if he had relied on his imagination. Instead, WS-E offers us the Gospel according to Theosophists, something about as appetising as sitting through a three-hourscientologist lecture today with bladder ache.

If you are after entertainment WS-E’s later book on egg-laying Lemurians is much closer to fun.

Any other examples of ‘remote viewing’ in the writing of history? Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com is all for looking.

***

24 Feb 2010: Invisible is on this one: ‘Remote viewing’ in the field of history. Not presented as fiction, but Frederick Bligh Bond’s The Gates of Remembrance. ‘Dictated’ by dead Glastonbury monks via automatic writing, and presenting his archaeological findings based on those tips from the Beyond. Also A.J. Stewart (Ada Kay) who, the night before a visit to Flodden Field, ‘flashed back’ to the death of King James IV of Scotland. She came to believe that she was the reincarnation of the King and wrote Falcon – The Autobiography of His Grace James the IV King of Scots and Died 1513 – Born 1929 from her ‘memories’ of being the King. And Joan Grant, who wrote Winged Pharaoh and several other ‘prior life autobiographies’ dictated while in a trance state. Thanks Invisible!