Sex Life of Unicorns February 5, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Medieval , trackbackUnicorns have a claim, in Beachcombing’s mind, to be the most interesting of all mythical creatures. There is, after all, a fascinating combination of the mundane – the unicorn is surely based on the rhinoceros? – and the fantastic: think of all that nonsense about a dilating horn and floating hooves. Then there is the unicorn’s appearance in so much modern fantasy and yet its antiquity in the earliest carvings from the Middle East. And so, by way of tribute Beachcombing wants today to ‘problematise’, as they say in all the best academic journals, one small aspect of this creature’s natural history, unicorn nooky.

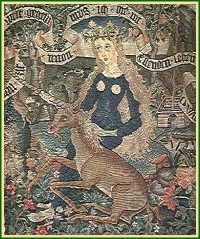

Now many readers at this point will recall how uninterested unicorns are in any form of fornication. And certainly the Christian tradition insisted on this for the unicorn was read as a symbol of Christ. Unicorns were gentle creatures who could be tamed only by a virgin, pure of heart. The unicorn would – the subject this of tens of medieval poems and images – come and lay its head on the virgin’s lap and allow her to caress it. This, naturally, gave hunters a great chance to creep up and lay their filthy hands on the purring unicorn who would then be led away into captivity: its valuable horn being sawn off and sold for a fortune to kings who would grind down the bone and feed it to syphilitic mistresses and leprous cousins.

The earliest version of this legend – at least in the form known to medieval Europe – appears in the Greek Physiologus. Beachcombing says ‘appears’. In fact, this text, dating from c. 150-400 AD – has not survived (another post, another day). But translations into many languages ranging from the loose to the absurd have made it through and from there we can deduce the original form or at least make informed guesses.

However, there is one unexpected variant on this story that suggests that the chaste unicorn is something of a legend within a legend. It appears in the Syriac ‘translation’, one of the earliest:

*There is an animal called dajja, extremely gentle, which the hunters are unable to capture because of its great strength. It has in the middle of its brow a single horn. But observe the ruse by which the huntsmen take it. They lead forth a young virgin, pure and chaste, to whom, when the animal sees her, he approaches, throwing himself upon her. Then the girl offers him her breasts, and the animal begins to suck the breasts of the maiden and to conduct himself familiarly with her. Then the girl, while sitting quietly, reaches forth her hand and grasps the horn on the animal’s brow, and at this point the huntsmen come up and take the beast and go away with him to the king. – Likewise the Lord Christ has raised up for us a horn of salvation in the midst of Jerusalem, in the house of God, by the intercession of the Mother of God, a virgin pure, chaste, full of mercy, immaculate, inviolate

Beachcombing is no Catholic but he is rather scandalised by the hussy that catches the unicorn here being compared to Mary. The unicorn ‘throws himself upon her’ (like Zeus on Europa?). The girl ‘offers… her breasts’ which the unicorn sucks upon and the unicorn ‘conducts himself familiarly with her’. Then there is that final grasping of the horn on the animal’s brow… Forget the weak Christian gloss at the end and ‘pure and chaste’: this story is something quite different from maid Marion in the wooden bower with hunters whispering to each other in the bushes.

So where does this story come from? Well, it is unlikely that it appears in the original Greek Physiologus – though not impossible. It is also unlikely that this is the invention of a later Syriac writer. It is conceivable that a monkish writer might have left such a curious account alone, but virtually inconceivable that a monastic scribe would have been allowed to introduce zoophiliac fantasies unless there was some precedent for them.

The easiest solution – that as Beachcombing knows from long and painful experience is not always the right one, Occam’s razor is decidedly blunt – is that we have a local folklore version of the tale that predated the chaste virgin story and that forced its way into the text with the authority of tradition. It is perhaps the Greek version of Physiologus and most European derivatives that ‘lie’: the unicorn was not a purring Christ-like animal but a randy quadruped.

Other interpretations? Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com