Antique Christians in Furthest China October 7, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval, Modern , trackback Beachcombing has often visited in these pages his favourite WIBT (‘wish I’d been there’) moments from history. And today he takes the gentle reader to another this time in China in honour of his mother and step-father who have recently fled the dominions for a holiday in the Far East.

Beachcombing has often visited in these pages his favourite WIBT (‘wish I’d been there’) moments from history. And today he takes the gentle reader to another this time in China in honour of his mother and step-father who have recently fled the dominions for a holiday in the Far East.

It is 1625 and the gutsy Portuguese Jesuit, Álvaro de Semedo finds himself in Xi’an in eastern China, face to face with an antique inscription.

Of course, travellers from the west often came face to face with inscriptions in foreign lands so why should this particular event give Beachcombing goose bumps? The reason is that Semedo could trace on the face of the stele Chinese characters that described how Christians had penetrated China a millennium before. In fact, poor Álvaro must have realised as he moved his fingers under the words carved there that he was not a pioneer, but a johnny-come-lately.

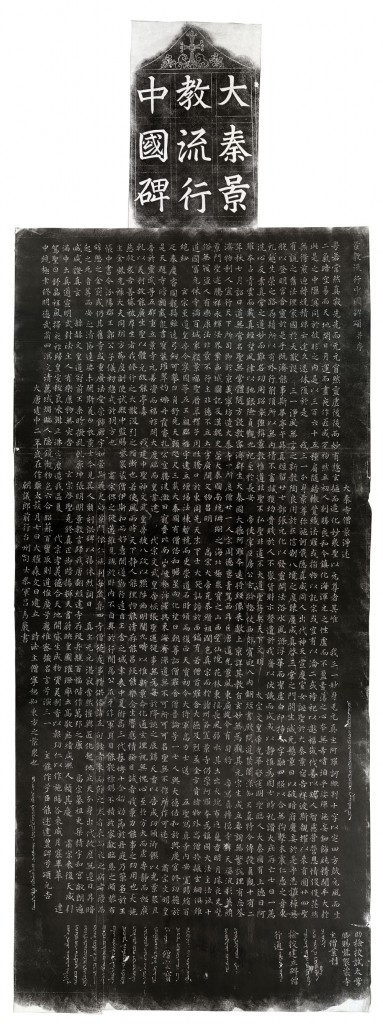

The stone – often called the Nestorian Stone – was put up in 781 after Christianity, ‘the luminous religion’, had put down roots in Tang China. Indeed, it gives the names of the faithful and a bishop who seems to have owed his allegiance to the Church in Persia. It also gives our best evidence that Christians had first penetrated eastern China in the seventh century: it describes, in fact, a missionary called Alopen, who beat Álvaro de Semedo to China by nine hundred years.

The Nestorian Stone needs to be put with the evidence of early Christian missions into eastern Africa, southern India and parts of central Asia that left behind Christian communities that either remained isolated from what Beachcombing thinks of as mainstream, medieval European Christendom, or, as in China, died out altogether.

Now these far flung versions of Christianity – the lost Christianities that Beachcombing was never taught about at Sunday School – were often ‘strange’ by European standards. Chinese Christianity, to judge by the Nestorian Stone was no exception. For one, their Christianity was – as the name of the stone suggests – Nestorian, with an interpetation of the Trinity that would have led to judgments of heresy, hysteria and condemnations of exile in the early medieval West.

But Beachcombing is not going to plunge into a debate here about the nature of Christ. (Procopious: ‘I consider it a sort of insane folly to investigate the nature of God’). He wants, instead, to enjoy for a few more moments the Portuguese Jesuit looking at himself in the strange distorting mirror of the stele, wondering at the Persian and other missionaries who had brought his own religion almost to the Sea of Japan and who had so resolutely failed. Perhaps Semedo, later in his life, even stumbled on the report of a monk returning from China in 986, who brought the news that only one Christian survived in the country.

Beachcombing’s inner child loves examples of Christianity in the wrong place and the wrong time: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com