Life on Mars and Other Stories September 14, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback Beachcombing has always had a bit of a thing about Percival Lowell (1855-1916) word-smith, Orientalist (author of Noto, 1891) and Ivy League rebel. And of all Lowell’s accomplishments none stand as high in Beachcombing’s estimation as Lowell’s theories on Mars set out in three books – all happily now available in pdf form: Mars (1895), Mars and Its Canals (1906), and, perhaps best of all, Mars as the Abode of Life (1908).

Beachcombing has always had a bit of a thing about Percival Lowell (1855-1916) word-smith, Orientalist (author of Noto, 1891) and Ivy League rebel. And of all Lowell’s accomplishments none stand as high in Beachcombing’s estimation as Lowell’s theories on Mars set out in three books – all happily now available in pdf form: Mars (1895), Mars and Its Canals (1906), and, perhaps best of all, Mars as the Abode of Life (1908).

The titles give some idea of the lush undergrowth into which we are about to stray…

Lowell came to astronomy fairly late in life and only began to dedicate himself to its study from 1893 when he was in his forties. But he did so with energy, iniative and wealth – he was, after all, one of the Boston Lowell’s, a colonial age family who had been present, with gold in their pockets, at every turn of American history.

With this wealth Percy built an observatory at Flagstaff in 1894 and watched the heavens from an elevated spot with no city lights to pollute viewings. Lowell famously wrote that telescopes should see and not be seen: in other words results, based on careful siting, not impressive-looking hardware were what mattered.

His great love was Mars and he studied this planet – particularly in periods of opposition – with passion and was particularly interested in ‘non-natural’ traces there. Indeed, his books are littered with references to ‘oases’, ‘nodes’ and, of course, that old Martian favourite canals.

Canals…

Lowell, who had an extremely sharp, well-disciplined mind is, in fact, a case study in how reasoning can go horribly wrong and those damn canals were at the bottom of it.

Giovanni Schiaparelli had introduced canals to the study of Mars in 1877 when, during the opposition, Schiaparelli had seen long lines on the surface of the planet.

Schiaparelli used the neutral canali in Italian that would be best translated into English as ‘channels’. But the word was translated into English as ‘canal’, a word that suggests, nay, demands intelligent agency: red-navvies working under a Martian heaven.

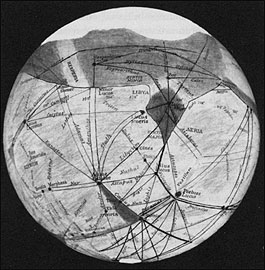

Lowell was well aware of the mistranslation, but he nevertheless deduced, to his own satisfaction, that the canals had been built. They had been built, he decided, by a dying civilisation on Mars that wanted to drain water from the icy poles towards the equator in harvest season. What astronomers were seeing, argued Lowell, were not lines in the deserts but blooming vegetation around those lines as water filled the channels: for a map see the image above.

It’s Beachcombing’s sad duty to report that what astronomers were actually ‘seeing’ was an optical illusion. The canals were small points on Mars that linked together when viewed from a distance. But, though this suggestion was already around in the early 1900s, Lowell was able to brush these counter-theories aside. He could argue that other scientists lacked his clear view from Flagstaff.

Lowell managed to get away with a great deal in his twenty years of astronomy precisely because he could wave ‘remote and elevated’ Flagstaff in his foes’ faces. Lowell saw, it was argued, better than astronomers in other observatories and, at least, at the beginning few dared contradict him when his sightings were ‘off’.

From the canals Lowell built a whole series of secondary theories including the position of Martian settlements and even speculation about how long it would take a Martian to build the channels in question. Lowell would then – in his talks and his writings – leave science behind and end with a dirge about how Martian life was dying as water was leaving the red planet and how this fate awaited the earth too. There was something very fin d’siècle about Lowell’s Mars.

Read Lowell’s books on Mars today and you will be treated to exquisite prose and exquisite reasoning put to the wrong ends.

Lowell’s consolation are his ‘children’. His books on Mars fertilised two disciplines: science fiction (War of the Worlds anyone…) and popular astronomy.

And reading his works in 2010 there is still an echo of that excitement that once filled the observatory in Flagstaff and that so animated his readers. Beachcombing remembers one passage in Lowell’s first Mars book where the astronomer sees a flash of light from the surface of Mars and deduces that the sun has glinted off a Martian glacier. Suddenly other worlds come alive and Mars exists as a landscape rather than a dot in the sky.

Beachcombing is always on the look out for eccentric nineteenth-century astronomical theories: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com